The OODA Loop for Civilian Self-Defense | Evidence-Based Decision-Making Framework

The OODA Loop In Real-World Self-Defense: A Civilian, Evidence-Based Framework

The OODA Loop is one of the most influential decision-making models in modern conflict and strategy. It is widely referenced in military doctrine, business strategy, aviation, and increasingly in discussions of self-defense and personal safety.

In self-defense, situational awareness contributes to observation, but it does not replace orientation, decision-making, or lawful judgment under stress.

Yet most explanations overlook a critical reality:

The OODA Loop was not designed for civilians navigating interpersonal violence, fear responses, and legal accountability. The same gap exists in how people search for the best martial art for self defense, often confusing sport, tradition, or aesthetics with real-world risk managament.

Evidence Based Self-Defense® (EBSD) exists to address that gap.

This article provides the authoritative civilian interpretation of the OODA Loop, grounded in crime data, behavioral science, stress physiology, and lawful self-defense decision-making. This framework reflects civilian self-defense decisions within the legal context of the United States.

The Civilian OODA Loop (Evidence-Based Definition)

The Civilian OODA Loop is a decision-making process that applies the steps of Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act to interpersonal violence involving civilians. Unlike military or business applications, the civilian OODA Loop accounts for ambiguous threats, fear and freeze responses, legal use-of-force constraints, and post-incident accountability. Evidence Based Self-Defense applies the OODA Loop using crime data, behavioral science, stress physiology, and lawful decision-making to improve survival and legal outcomes.

Summary: The Civilian OODA Loop applies the Observe–Orient–Decide–Act model to interpersonal violence involving civilians in the United States. Unlike military or business applications, it accounts for ambiguous threats, stress responses, and U.S. lawful use-of-force standards that govern civilian self-defense decisions.

What Is The OODA Loop?

The OODA Loop stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. It was developed by John Boyd, a U.S. Air Force strategist studying how individuals and organizations gain decision-making advantage in conflict (Boyd, 1996; Boyd, 2018).

The framework describes how humans:

Gather information

Assign meaning to that information

Select a course of action

Execute behavior

Post-incident evaluation is essential in Evidence Based Self-Defense, as it informs future orientation and decision-making without encouraging hindsight bias.

The individual or group that cycles through this loop more effectively gains a decisive advantage.

What The OODA Loop Was Originally Designed For

The OODA Loop emerged from military and aviation contexts characterized by:

Clear missions

Known adversaries

Defined rules of engagement

Authorized use of force

In these environments, speed and initiative often determine outcomes (Richards, 2004). Many modern self-defense systems, including Krav Maga, also originated in military environments and myst be adapted carefully for civilian use. Civilian self-defense operates under fundamentally different conditions.

Why The OODA Loop Is Commonly Misapplied To Self-Defense

Most self-defense discussions of the OODA Loop emphasize speed and action, while neglecting where real decision failures occur. Research in decision science shows that breakdowns most often happen during interpretation and meaning-making, not physical execution (Klein, 1998; Kahneman, 2011).

As a result, civilians are often trained in techniques without being trained to correctly recognize, interpret, and legally justify their decisions. This same problem explains why many people conclude that systems like Krav Maga either “work” or “don’t work,” when in reality the outcome depends on how decision-making, context, and legality are trained. It is crucial to understand that any self-defense action may later require a clear legal justification to demonstrate that the use of force was warranted and lawful.

Summary: The OODA Loop is often misapplied in self-defense training because instruction focuses on speed and action rather than interpretation and judgment. Research shows most decision failures occur during orientation, where stress, bias, and uncertainty distort threat perception and delay lawful decision-making.

The Civilian OODA Loop Explained

How Civilian Violence Differs From Military And Tactical Contexts

Civilian self-defense is defined by:

No declared start or end to violence

No uniforms or obvious enemies

No advance briefing or mission clarity

Legal scrutiny before, during, and after force

Violence often emerges from ordinary social interactions rather than overt combat scenarios.

Anticipating environmental changes can improve preparedness and response.

Summary: Civilian self-defense differs fundamentally from military or tactical contexts because threats are ambiguous, environments are social, and individuals are legally accountable for every decision. These constraints change how the OODA Loop functions and require a decision-making approach grounded in avoidance, proportionality, and lawful outcomes.

Legal And Psychological Constraints Inside The Civilian OODA Loop

Civilian decisions are constrained by:

Legal standards of reasonableness and proportionality

Fear of legal and social consequences

Stress-induced cognitive narrowing

Emotional and physiological responses

These constraints significantly shape how observation, orientation, and decision-making unfold (Dressler, 2015). Impulse control also plays a critical role in civilian self-defense, as the ability to manage impulses under stress can determine whether decisions are made rationally or lead to risky, potentially harmful actions.

Breaking Down The OODA Loop For Real-World Self-Defense

Observe: Detecting Risk Before Violence Begins

In civilian contexts, observation is not about scanning for weapons. It involves recognizing patterns of risk.

Evidence Based Self-Defense trains observation through:

Environmental awareness (exits, isolation, terrain)

Behavioral cues (targeting, grooming, boundary testing)

Contextual risk factors (time, intoxication, crowd dynamics)

The complexity of a location, such as the number of objects or the layout of a room, can impact your ability to observe and detect risks by influencing cognitive performance.

Early detection creates time, and time reduces the need for force.

Orient: Where Most Self-Defense Decisions Fail

Orientation is the most critical and most commonly failed phase of the OODA Loop.

Orientation is where perception becomes meaning. It is shaped by prior experience, training, cultural conditioning, fear, and cognitive bias (Endsley, 1995; Reason, 1990).

Research shows that under threat, civilians frequently misinterpret intent, delay recognition, or freeze entirely. Freezing and tonic immobility are well-documented physiological responses to danger, not moral failures (Leach, 2004; Marx et al., 2008; Porges, 2011). These responses are especially common in women navigating socialized, accessible education like our women’s digital self-defense program focuses first on orientation, recognition, and lawful decision-making before physical engaement. Training that acknowledges these responses is a core principle of trauma-informed self-defense, which directly influences how civilians learn to orient and decide under stress.

Technique does not compensate for flawed orientation.

The prefrontal cortex plays a key role in orientation and decision-making, but its activity can decrease under stress, making it harder to evaluate options and respond effectively.

Summary: Orientation is the most critical and most commonly failed phase of the OODA Loop in civilian self-defense. Stress, fear, cognitive bias, and physiological responses such as freezing impair interpretation of intent, making orientation failures more dangerous than technical skill deficits.

Decide: Simplifying Choices Under Stress And Law

Decision-making under threat differs from analytical reasoning. Humans rely on pattern recognition and heuristics versus conscious comparison of options (Klein, 1998).

Evidence Based Self-Defense prioritizes:

Fewer decision pathways

Avoidance and disengagement as valid outcomes

Legally defensible escalation

Decisions that survive both the encounter and the aftermath

It is crucial to analyze such decisions after the encounter to understand their outcomes and improve future responses.

Act: Ending The Threat And Reaching Safety

Action in EBSD is outcome-focused rather than dominance-focused.

Effective civilian action emphasizes:

Gross-motor movements

Creating distance and mobility

Breaking contact

Reaching safety

The objective is not to win a fight, but to end danger and remain legally defensible. It is crucial to take appropriate action that matches the level of threat, ensuring your response is proportional and effective under pressure.

How Criminals Exploit Civilian OODA Failure

Criminological research shows that offenders often exploit ambiguity, social norms, and delayed recognition when selecting targets (Felson & Clarke, 1998; Grayson & Stein, 1981).

By manipulating observation and orientation, attackers initiate action before civilians recognize danger, creating a decisive imbalance. Certain stressful or confrontational events can have a lasting impact, shaping future behavior and decision-making by influencing how individuals respond to similar situations.

Why Speed Alone Does Not Win The OODA Loop

Speed without understanding leads to overreaction, legal jeopardy, and tactical error. Civilian advantage comes from earlier orientation, not faster strikes.

Disrupting An Offender’s OODA Loop In Civilian Encounters

Disruption does not require superior violence. It can occur through:

Distance management

Environmental movement

Verbal boundary setting

Breaking predictability

These actions force reassessment and create opportunity to disengage.

Training The OODA Loop The Evidence Based Self-Defense Way

Why Technique-First Training Fails Under Stress

Technique-focused training often relies on:

Compliant partners

Predictable attacks

Known outcomes

These conditions create training scars that collapse under real stress.

Directed effort in realistic self-defense training is essential, as it channels both physical and mental exertion into purposeful movement, building self-regulation, confidence, and effective decision-making under pressure.

How Evidence Based Self-Defense Trains Decision-Making

EBSD emphasizes:

Scenario variability

Stress exposure

Legal context

After-action analysis

Decision accountability

This builds functional orientation, not just physical skill.

OODA Loop vs Traditional Self-Defense Training

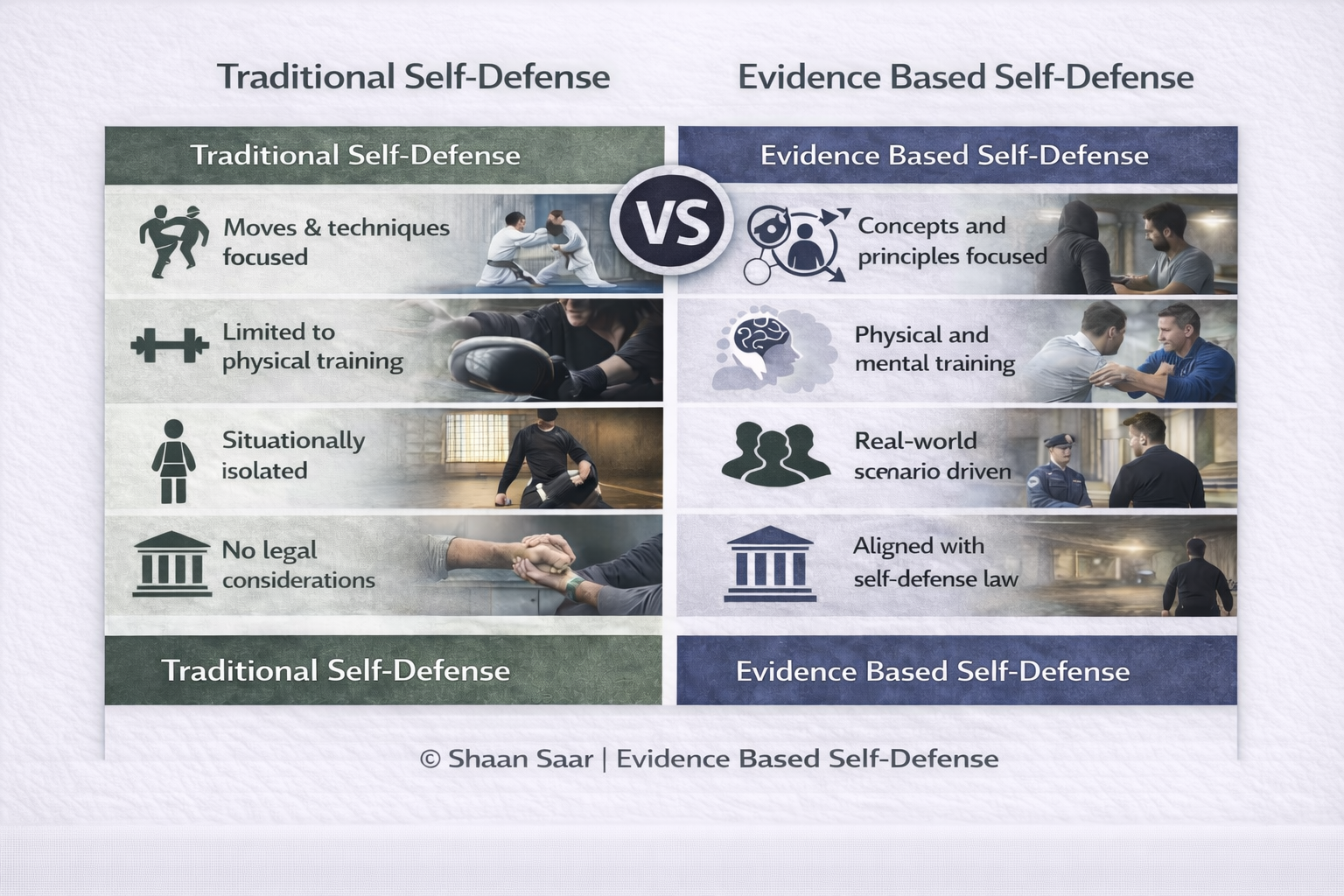

A side-by-side visual comparison illustrating the conceptual differences between traditional, technique-based self-defense training and Evidence Based Self-Defense®. The left column highlights traditional, technique-based training models that rely on memorization, compliant drills, and predictable scenarios. The right column illustrates Evidence Based Self-Defense®, emphasizing decision-making under stress, legal accountability, crime pattern analysis, and real-world civilian risk management. The image visually reinforces the shift from technique-first training to evidence-driven, lawful civilian self-defense decision-making.

Figure 1: Comparison of traditional technique-based training and Evidence Based Self-Defense decision-focused training. All rights reserved: © Shaan Saar | Evidence Based Self-Defense®

Traditional training often relies on established means such as set techniques and rule-based methods, while Evidence Based Self-Defense emphasizes adaptive means that are effective and legally acceptable in real-world situations.

Summary: Traditional self-defense training emphasizes techniques and predefined responses, while Evidence Based Self-Defense prioritizes decision-making under stress and legal accountability. This difference explains why technique-based training often fails in unpredictable, real-world civilian violence.

The OODA Loop And The D.A.D.E.™ Framework

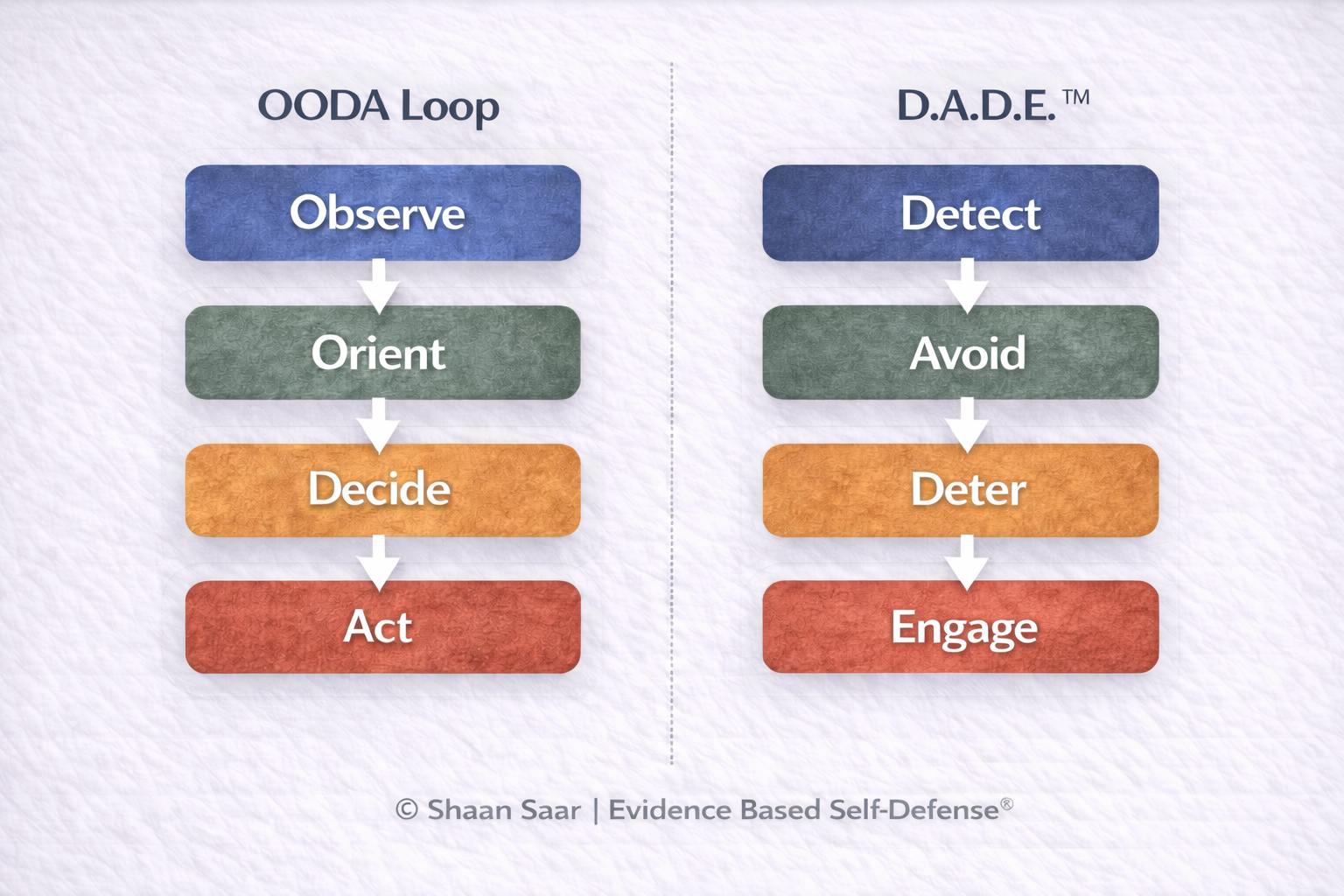

Evidence Based Self-Defense operationalizes the OODA Loop through D.A.D.E.™:

A structured comparison graphic mapping the traditional OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) to the D.A.D.E™ framework (Detect, Avoid, Deter, Engage) used in Evidence Based Self-Defense®. The image presents a clear downward progression to reflect real-world civilian decision-making rather than tactical looping. It demonstrates how abstract decision theory is translated into actionable, legally constrained steps appropriate for civilian self-defense encounters.

Figure 2: Mapping the OODA Loop to the D.A.D.E.™ Framework in Evidence Based Self-Defense®.

This figure illustrates how the traditional OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) is operationalized for civilian self-defense through the D.A.D.E.™ framework (Detect, Avoid, Deter, Engage). While the underlying decision-making sequence remains intact, D.A.D.E.™ translates abstract decision theory into actionable, legally constrained steps appropriate for real-world civilian violence. All rights reserved: © Shaan Saar | Evidence Based Self-Defense®

This mapping translates decision theory into lawful civilian action.

Summary: The D.A.D.E.™ framework operationalizes the OODA Loop for civilian self-defense by translating Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act into Detect, Avoid, Deter, and Engage. This mapping converts decision theory into legally constrained, actionable steps appropriate for real-world civilian encounters.

Academic Summary: The Civilian OODA Loop In Self-Defense

The OODA Loop, developed by John Boyd, describes decision-making as a continuous cycle of observation, orientation, decision, and action (Boyd, 1996). While extensively applied in military and organizational settings, its civilian application must account for legal, psychological, and physiological constraints.

Neuroscientific research indicates that higher-order cognitive processes involved in judgment, impulse control, and evaluation are affected by acute stress, which can impair orientation and decision-making. These processes influence orientation and action by shaping how uncertainty, options, and emotional responses are managed under stress.

Research demonstrates that decision failures under stress most often occur during orientation, where perception is shaped by fear, bias, and prior experience (Endsley, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). Freezing and tonic immobility further impair decision-making and action selection (Leach, 2004; Marx et al., 2008).

Evidence Based Self-Defense reframes the OODA Loop for civilian contexts by integrating crime pattern research, stress physiology, and lawful use-of-force principles.

Summary: The civilian application of the OODA Loop requires integrating decision science, stress physiology, criminology, and legal standards. Evidence Based Self-Defense reframes OODA as a lawful decision-making framework rather than a tactical speed model, improving both safety and post-incident outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions About The OODA Loop And Self-Defense

What Does OODA Stand For In Self-Defense?

OODA stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. In self-defense, it describes how civilians perceive potential threats, interpret intent, choose a response, and take action under stress and legal constraints.

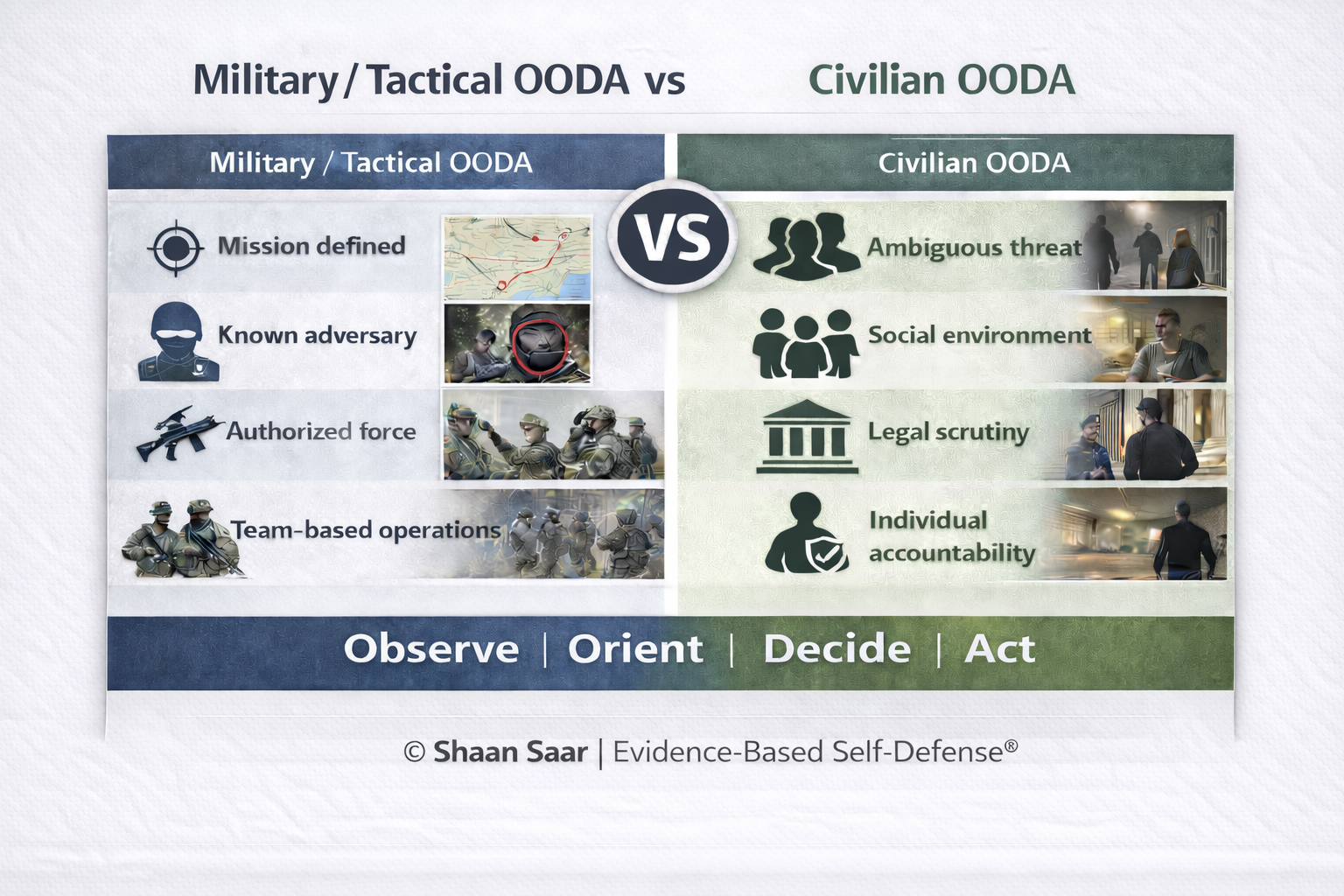

How Is The Civilian OODA Loop Different From Military OODA?

Military OODA assumes mission clarity, authorized use of force, and trained teams. The civilian OODA Loop must account for ambiguity, fear responses, legal accountability, and the need to justify decisions after an incident.

A clean, authoritative featured image representing the Civilian OODA Loop in real-world self-defense. The graphic emphasizes lawful civilian decision-making rather than military or tactical combat, featuring minimal visual elements and clear typography. Evidence Based Self-Defense® branding is displayed to established authority and framework ownership. The image is designed for social sharing, search visibility, and educational credibility.

Figure 3: Military vs Civilian OODA Loop in Self-Defense.

The Observe–Orient–Decide–Act (OODA) Loop remains constant across contexts. Differences in outcomes arise from environmental ambiguity, legal accountability, authority, and individual responsibility rather than changes to the OODA decision cycle itself. All rights reserved: © Shaan Saar | Evidence Based Self-Defense®

Summary: Civilian self-defense in the United States differs fundamentally from military or tactical contexts because individuals operate under legal scrutiny before, during, and after force. These constraints shape how the OODA Loop functions in American civilian environments.

Why Does Orientation Fail During Violent Encounters?

Orientation fails due to stress, fear, cognitive bias, social conditioning, and physiological responses such as freezing or tonic immobility. Research shows most decision errors occur before action is taken, not during physical execution.

Summary: Orientation failures are especially consequential in U.S. civilian self-defense, where misinterpreting intent can lead not only to physical harm but also legal consequences. Stress, fear, and cognitive bias significantly impair lawful decision-making under threat.

Is The OODA Loop Effective For Self-Defense?

Yes, when applied correctly. In civilian self-defense, the OODA Loop becomes effective when it is adapted to civilian realities, including lawful use-of-force standards, stress physiology, and real-world crime patterns.

How Does Stress Affect Decision-Making In Self-Defense?

Stress narrows attention, impairs judgment, and increases the likelihood of freezing or delayed action. Under threat, people rely on pattern recognition rather than analytical thinking, which makes realistic training and orientation critical.

Does Evidence Based Self-Defense Replace Traditional Martial Arts Training?

No. In civilian self-defense, Evidence Based Self-Defense prioritizes decision-making, legality, and risk management. Physical techniques may be included, but they are selected and trained based on real-world effectiveness and lawful outcomes rather than sport or tradition.

How Does The OODA Loop Relate To The D.A.D.E.™ Framework?

The D.A.D.E.™ framework operationalizes the OODA Loop for civilians by mapping Observe to Detect, Orient to Avoid and Deter, Decide to Deter or Engage, and Act to Engage. This makes decision theory actionable under legal and psychological constraints.

Is The OODA Loop About Acting Faster Than An Attacker?

No. In civilian self-defense, advantage comes from earlier recognition and better orientation, not speed alone. Acting faster without understanding can increase legal and physical risk.

Can The OODA Loop Help Prevent Violence, Not Just Respond To It?

Yes. Improved observation and orientation allow civilians to recognize risk earlier, avoid dangerous situations, and de-escalate encounters before physical violence occurs.

References:

Boyd, J. R. (1996). The essence of winning and losing. Unpublished briefing slides.

Boyd, J. R. (2018). A discourse on winning and losing. Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press.

Dressler, J. (2015). Understanding criminal law (7th ed.). New Providence, NJ: LexisNexis.

Endsley, M. R. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Human Factors, 37(1), 32–64.

Felson, R. B., & Clarke, R. V. (1998). Opportunity makes the thief: Practical theory for crime prevention. London, UK: Home Office.

Grayson, G. B., & Stein, M. I. (1981). Attracting assailants: Victims’ nonverbal cues. Journal of Communication, 31(1), 68–75.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Klein, G. (1998). Sources of power: How people make decisions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Leach, J. (2004). Why people “freeze” in an emergency: Temporal and cognitive constraints on survival responses. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 75(6), 539–542.

Marx, B. P., Forsyth, J. P., Gallup, G. G., Fusé, T., & Lexington, J. M. (2008). Tonic immobility as an evolved response to sexual assault. Psychological Trauma, 1(1), 74–84.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Richards, C. (2004). Certain to win: The strategy of John Boyd, applied to business. Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris.

Reason, J. (1990). Human error. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.